Many Dunedin residents will be familiar with the small village of Portobello which sits about twenty kilometres from the city centre on the inland side of the Otago Peninsula, as well as the marine laboratory at the end of the Portobello Point which also used to house a public aquarium.

The laboratory, which opened in 1904, was originally founded as a fish hatchery, at the instigation of George Thomson, a naturalist and high school biology teacher, with the aim of introducing commercially valuable European marine species, including European lobster, edible crab, turbot and herring, into New Zealand waters, in the same way that many other European terrestrial species had also been ‘acclimatized.’ This project was managed by the Portobello Marine Fish Hatchery Board and funded by the Marine Department, but after more than thirty years of work none of these introduced species managed to establish themselves and in 1951 the premises were handed over to the University of Otago.

The fish hatchery was in an excellent central location in the middle of the harbour for carrying out marine research, but until a road was built out to the end of the point in 1956, the only access was by boat. In 1960 the university replaced the old hatchery with a new building, complete with a public aquarium and there have been a number of significant additions to the laboratory over the last 70 years.

In 1951 Dr Betty Batham, was appointed the lab’s first director but the appointment of a female academic to a leadership role at a university laboratory was a controversial move in those days and not everyone approved. This talented scientist was born in Dunedin in 1917 and was one of the earliest women to graduate from the University of Otago with a top notch science degree. Later she completed her doctoral studies at the University of Cambridge, where she did some pioneering work into the anatomy of sea anemones, as well as working as an assistant to Carl Pantin, Professor of Zoology from 1959 to 1966.

I remember Betty well because she was a good friend of my mother, Dr Pauline Mahalski.

When they met, Pauline was still a science teacher at Queens High School but she had some solid academic credentials of her own and being a secondary school teacher wasn’t enough. After a meeting with another local marine scientist, Bob Weir, she began to conduct her own long term study into the habits of the mud crabs which live on the peninsula.

There are two main species, the tunnelling mud crab (Helice crassa) and the stalk-eyed mud crab (Macrophthalmus hirtipes), but hairy-handed crabs (Hemigrapsus crenulatus) are also present in the intertidal zone. These crabs are both scavengers and predators who like to hide in their burrows at low tide and only come out to feed and socialise when the tide is high. All three species are also important prey for fish, sharks, octopuses, birds and seals.

Whenever she got a day off from teaching, mum would drive the family’s old blue Beetle out along the peninsula to her favourite spot at Papanui Inlet and sit there for hours watching crabs and taking notes. I got dragged along on many of these expeditions and I had no choice but to find my own ways of entertaining myself while she ‘worked’ because in my little family you just weren’t allowed to say you were bored. There wasn’t any internet back then so I used to wander around the area and watch the local birds and I think this is also around the time when I first started to get really serious about collecting bones.

Mum also used to like watching crabs when we went overseas and one time I made quite a lot of money in Fiji when I devised a way of trapping fiddler crabs for her at $5 each. The females of the species look like normal crabs but the males have one pincer which is much bigger than the other which they wave around a bit like someone playing the fiddle. These bad boys like to wave their giant super-sized pincers around to both threaten other males but also to entice the local ladies to check out the etchings in their burrows.

Despite her extra curricular research, Pauline took her day job seriously, and, with the help of Betty, she used to organise regular field trips for her Year 11-12 students out to the lab to study coastal marine life. Occasionally some of the students would even stay the night at the Biologist’s Cottage up the hill from the lab and my mother would organise for a powerful light to be hung off the wharf to attract some of the light-sensitive denizens of the harbour. It wouldn’t take long before they’d be a huge swarm of tiny animals swimming around in tight circles underneath the light and trying to eat each other before they were snaffled up by a student with a dip net. To me the most fascinating creatures were the mantis shrimps, the tigers of the local crustacean community, who, like the mud crabs, prefer to hide in their burrows during low tide and only come out to feed when it’s high. The students were encouraged to bring the most interesting specimens into the lab to look at under a microscope and then try to draw and describe them while they were still alive.

Betty didn’t always feel appreciated in the patriarchal world of the university. After a number of internal battles with the university she began to succumb to depression and in 1974 this remarkable woman disappeared near Seatoun in Wellington harbour in what was either a diving accident or intentional suicide. The coroner left the verdict open and one of Betty’s protégés, Dr John Jillett, was appointed the new director of the lab.

It was around this time I first started to compete in the regional science fairs which were held at Otago Museum every year and thanks to Dr Jillett, I was lucky enough to be able to use some free space at the lab to run some of my little experiments. At this time there was only a tiny number of full time staff and an equal number of graduate students and it’s some of these people I really want to talk about today.

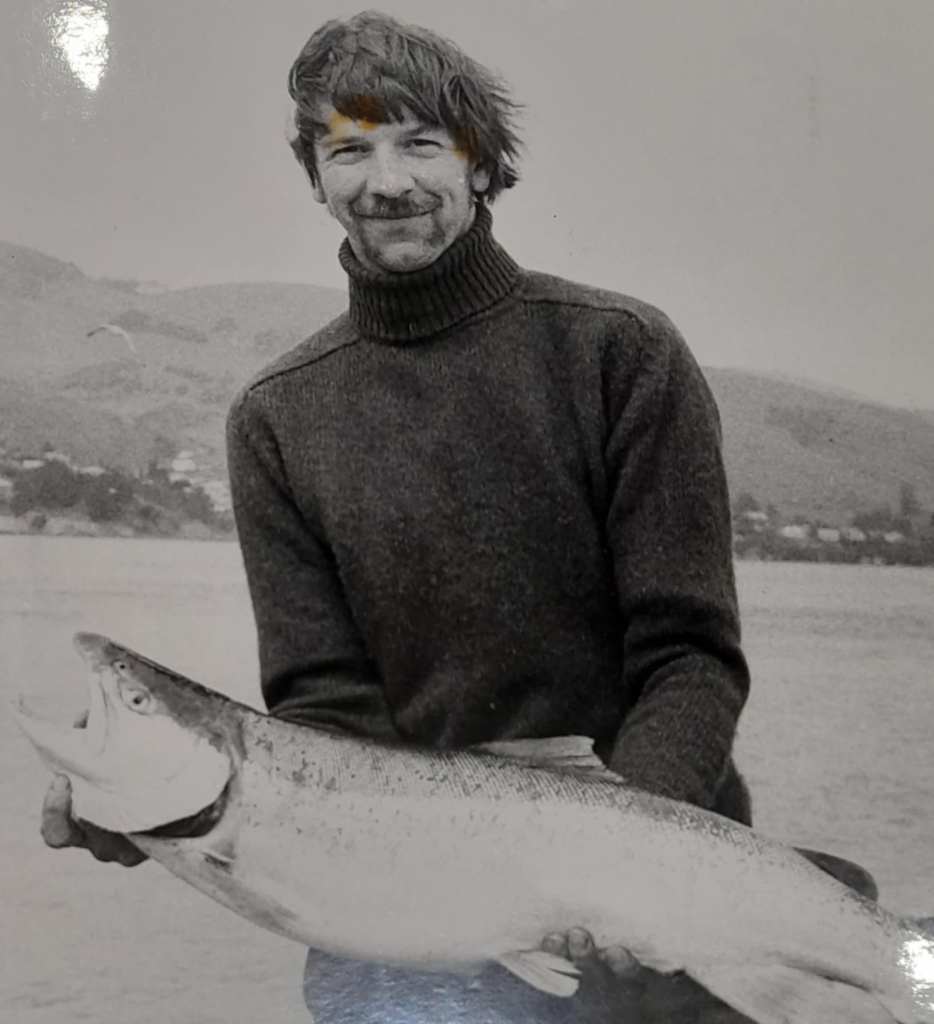

In 1976 I was inspired by the movie, ‘Jaws’ and decided to ‘study’ the Otago harbour’s dogfish population. These small sharks come into the harbour every year to birth their pups in spring and summer. There are two main species – the spotted dogfish and the spiny dogfish and I was interested to see what these young sharks were eating. To be frank our family also used to like eating them too so I arranged to borrow a set net from the lab which I moved around the harbour during the summer months catching lots of young sharks and opening them up to find out what they’d been feeding on. The net also caught a number of other species including kahawai, barracuda and one time, a very nice sea run trout.

I found the baby sharks were mainly feeding on crabs, small fish and marine worms. The person who arranged for me to borrow the net was the marine station caretaker, Jack Jenkins, and even through I was only thirteen, we soon became good friends.

I always think of Jack as some kind of maritime version of Barry Crump and in many ways he had a very similar background. Born in 1927, this good keen man was born in Romahapa (near Balclutha) but was raised at both Broad Bay and Warrington, so he was about as local as they come. Later he moved to the West coast, where he worked variously as a rabbitter, a cattle musterer, and a tramping guide. In the fifties and sixties he started fishing for whitebait in the Big Bay area and he maintained a couple of huts in the area for years. In 1968 he was appointed the marine lab’s first fulltime caretaker/technician and moved into the caretaker’s cottage up above the lab with his young family. His main duties were to assist the staff and students with their research and to look after the public aquarium.

As a teenager, I was very grateful to be able to hang round the lab and to try and ‘pay my way’ I used to try and help the scientists and the students with their work by recording data, sorting samples and assisting on the boats when people were out collecting water or specimens for their various projects. I used to go out to the lab every chance I got and I’d generally follow Jack around until he took the marine stations little motorboat out on some exciting mission or other. In summer he used to set a couple of nets close to the mole at the harbour entrance to catch dogfish specimens for the university’s first year biology students to dissect, as well as specimens for the public aquarium and food for its occupants but I think perhaps the most important reason was to secure an ongoing supply of delicious fish for his family and the staff.

Sometimes Jack would let me drive the boat as we zoomed up the harbor and back to the nets. It was always super exciting to pull them in and see what they’d caught and occasionally the catch exceeded all expectations. In 1974 he caught a huge white shark and the following year he caught an even bigger one! The latter was over four metres long and had a massive girth, the reason for which became apparent when it was dissected by John Darby, the assistant director of Otago Museum, who found a whole metal crayfish pot in its hugely distended stomach, along with a ray and some crabs. If Jack hadn’t caught the shark the pot would have killed it as it was much too big to regurgitate. You can still see its huge jaws on display at Otago Museum today.

In 1976 yet another giant shark ended up the nets. This time it was a basking shark, the second biggest shark species in the world and a very rare visitor to this part of the world. Basking sharks are harmless plankton feeders but white sharks feed on seals and sometimes they seem to mistake a human for their favourite prey.

The harbour entrance is a breeding site for local fur seals so I’m always a little bit surprised that many people do their dive training in an area when white sharks are occasionally known to be present. I suspect there might have been more sharks back then because a local fish processing plant was dumping fish offal directly off Taiaroa Head.

It’s extremely rare for a diver to be attacked by a white shark but in 1968 spear fisherman. Graeme Hitt, was attacked by a large shark and sadly he didn’t survive. Between 1964 and 1971 there were five shark attacks around Dunedin. The last one occurred on March 30, 1971, when surfer Barry Watkins (16) was bitten by a large white shark off St Clair beach but luckily the shark seemed to be more intent on chewing on his board, the remains of which can also be found in the Otago Museum collection. Mr Watkins was fortunate not to lose any limbs but he did need 90 stitches from knee to thigh in one of his legs and apparently it still aches sometimes when it is cold. The ocean temperatures close to the coast became briefly colder around this time and this could have been the reason for the high number of white sharks in the area because they prefer colder water. Fifty years ago the Southland current came much closer to the coast than was normal. Now, due to climate change, this cold water current is being pushed ever further from the coast by the warm waters of the Tasman current, which means less white sharks, but also less food for some of our favourite coastal species including the hoiho, who are having to swim further and further out to sea to get to the cold water zone where they feed.

One time Jack and I pulled up a giant conger eel with a head the size of a Rottweiler just around the corner from the lab and I remember it thrashing around in the bottom of the boat while we both stood on the sides and tried to avoid being bitten by this extremely intimidating animal. After it had calmed down a bit from lack of oxygen, I kept a spray of water over its gills and we took it back to the aquarium and released it into the biggest tank to join another big conger that was already in residence. I’d be amazed if any visitors to the aquarium ever saw either of them apart from maybe their heads because the only time these giant eels would come out from behind the rocks and swim around was at night time when the aquarium was closed.

Shark attacks and giant eels aside, life at the lab was great and according to Jack’s daughter, Kay, their family had great life, swimming, fishing, collecting kai moana, exploring nearby Quarantine island, and many other adventures. On a couple of occasions I joined the family for dinner and I vividly remember a gigantic pig called Arnold which Jack had picked up as a baby in the wild. This terrifying animal would rear up out of its pen behind the cottage and snap its massive jaws at you like a scene from a horror movie.

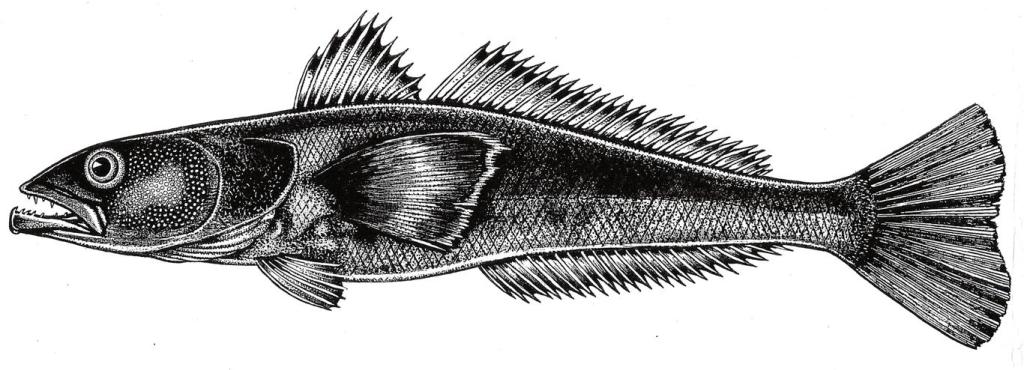

In 1981 Jack was given the opportunity to take some live blue cod down to McMurdo base in Antarctica as part of a study being conducted in the anti -freeze properties of cod blood in a study comparing the composition of blue cods’ blood with that of the Antarctic cod, nowadays better known as the Antarctic Toothfish. Some fifteen years later toothfish went on to become a highly sought after commercial species and now every year a host of countries rush down to the Ross Sea in summer to target this increasingly rare high value fish.

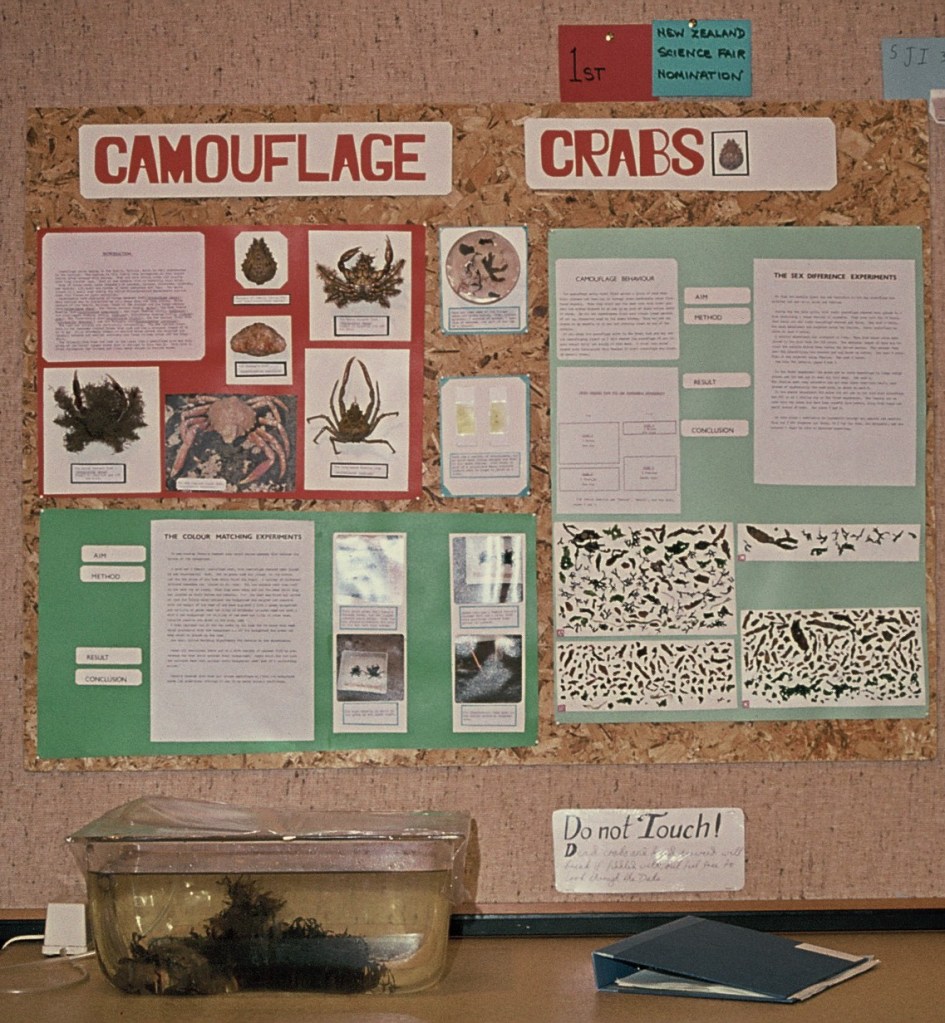

In 1977 I conducted my second series of experiments using the lab’s facilities and equipment. The year before I’d won the local statistics prize with my dogfish study but it wasn’t enough for me and for this second series of experiments I set up some tanks at the lab which I filled with local camouflage crabs representing the two most common species.

These sneaky crustaceans like to adorn themselves with seaweeds, sponges and even anemones to try and make themselves invisible and they’re very good at it.

Over a few months I ran a series of experiments in which I placed one species and then the other in a tank covered all the way around with red or green cardboard. The crabs were supplied with food and both red or green seaweed with the aim of seeing if they would choose the correct seaweed colour to match the overall background colour of their tanks. I also ran the same experiments with male crabs and female crabs to see if that made any difference.

My experiments seemed to indicate that both species of crabs either couldn’t or wouldn’t use the correct colour seaweed to match the exterior colour of the tanks but I noticed the female crabs were much better at cutting up their seaweed into nice little pieces and neatly applying it to their bodies than the boy’s who’d just tend to jam it on in big uncut pieces a bit like the way I dress myself. My theory was this could be because female crabs have smaller and more delicate pincers than the males but we all know that women are much more interested in looking good than men. At the end of the experiments I came to conclusion that another year or two’s research would be needed to come to any firm conclusions but I entered my research into the science fair none-the-less and got first in the local and fifth in the national competition that year. The following year my family went overseas but when we got back I continued to go out to the lab with the pretence of making myself useful, but really so I could hang out with all of these interesting adults and go out on boats.

I also started working part time for Jack, helping him to make metal crayfish pots in a small building he had in Portobello. I always wondered if it was one of Jack’s crayfish pots which had ended up in that shark as he was one of the main people making crayfish pots in the area. Truth be told I was absolutely terrible at metal work but I think Jack tolerated me because we enjoyed each others company. In 1986 my hero retired at age 59 but sadly he didn’t live long enough to enjoy it and I was very sad when he suddenly died from cancer shortly afterwards.

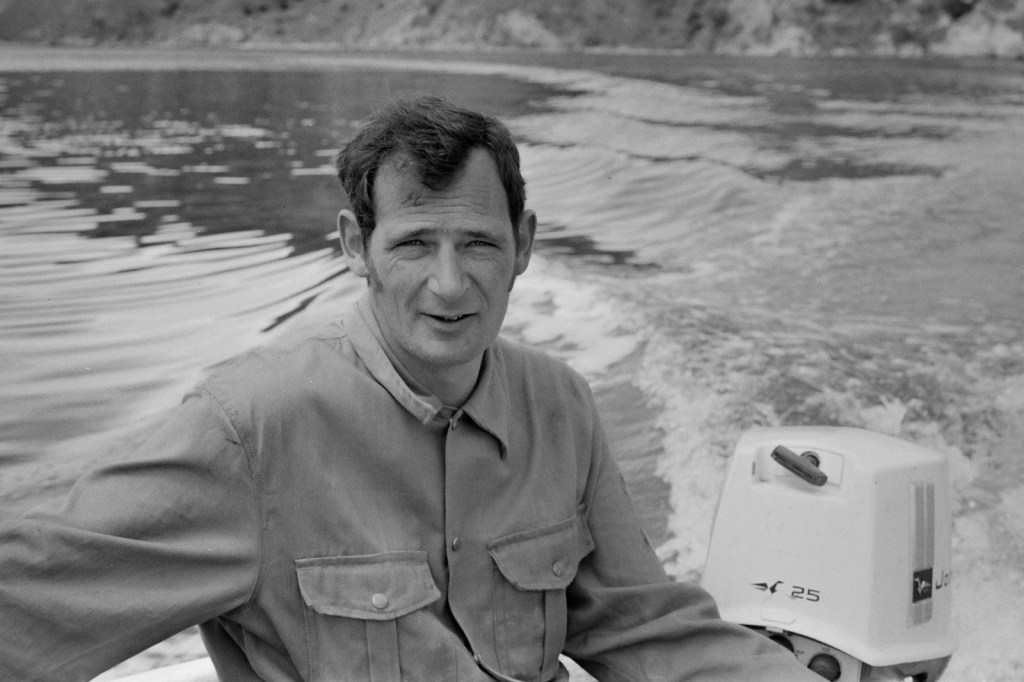

If Jack had a counterpart at the marine lab it was definitely Bill Tubman, the skipper of the lab’s research vessel, the Munida, which was named after a species of squat lobster which came into the harbour in huge numbers every summer.

This fifteen metre purpose built research boat was funded by a grant from The Golden Kiwi Lottery (the big national lottery before Lotto) and it was built in Nelson by Nalder and Biddle and fitted out in Lyttelton in 1966 before beginning its service for the lab. The boat was kitted out for oceanographic research and marine sampling and was used for many years by a succession of scientists and graduate students to sample both local water conditions and marine life.

Bill crewed on a mate’s boat, the Arabella, before working on the Ranger which he later owned. He sold the boat in 1957/8 and opened a fish shop in Green Island. He didn’t retire, worked at Cadburys, the Roslyn Mill and Holsum bakery from where he got the job as skipper of the Munida. The position was full time and was paid through a Golden Kiwi grant same as the boat.

Bill originally came from Warrington where he’d worked at the local grocery store and in the late forties he crewed on a local fishing boat, the ‘Arabella’ before crewing on the ‘Ranger’ which he later owned, before opening a fish shop in Green Island. At some point he moved to Auckland, where he became the skipper on the police launch before moving down to Fiordland to fish for lobster. In 1966 he became the skipper of The Munida, a full time position, which was also paid for by a Golden Kiwi grant.

Bill also tolerated my company and sometimes he’d let me come out on the Munida as an honorary deckhand. On one memorable two day trip we went down to the Nuggets to sample storm clams for a graduate student. Every hour or so the dredge would go down to the bottom before coming back up to the surface every twenty minutes or so filled with all sorts of interesting things, including baby octopuses, strange fish and all sorts of other bizarre bottom dwellers. My job was to help sort out the clams and shovel the rest off the side with a big metal shovel. The dredging went on into the night and the next day with barely a let up and I was starting to get very tired when suddenly – Whammo! I had some kind of a spasm like a big electric shock, but at first I thought I’d had some kind of brain fart, so, after recovering myself I jammed my shovel into the pile again. Big mistake! The same thing happened! Whammo! I could see Bill laughing until he was kind enough to alert me to the fact that I was poking an angry electric torpedo ray! After donning some rubber gloves he assisted it back into the deep and I got some new respect for an animal which can actually electrocute you!

Marine lab director, John Jillett, was right when he described Bill as like “an uncle to many of the students” and I know that he was proud of the prominent positions many of the students who came out on the boat gained later in other parts of the world. He remembers one in particular for her suggestion that the ship’s toilet (if you could call it that) needed a seatbelt and it was certainly was very difficult sometimes to stand up in the back of boat, let alone have a sleep or a private toilet break. Bill worked as the Munida’s skipper for twenty years before retiring in 1985.

John Jillett wasn’t just the director; he was also a scientist in his own right and an expert on Munida, along with his colleague Barbara Williams. This species, Munida gregaria, are more commonly know as the gregarious squat lobster and they’re found along the eastern seaboard of the south coast of New Zealand, around the southern coast of Tasmania and in a few other locations around the southern part of South America. They’re also sometimes referred to as lobster krill, because they look a bit like baby lobsters but unlike lobsters they’re found in swarms close to the surface like krill. When I was young, massive schools of Munida would come into the harbour every summer and sometimes they’d blow ashore by the thousands and stain the beaches red, providing a huge source of food for other marine animals coming into the harbour to feed and breed.

Another person studying Munida was the American graduate student, John Zeldis and many years later I ended up working for him in Wellington at the National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research at Greta point in Wellington. He was running a long-term study trying to correlate the recruitment of young snapper into the adult population by analyzing the number of eggs in the water every year and the amount of food available for the young fish to try and predict the number of catchable snapper in the near future.

Charlie Boyden was an English scientist who was renowned for his work on cockle’s and other shellfish. He had developed a method of monitoring feeding in limpets, those triangular shaped shellfish you often find on the rocky shore. Right next to the wharf at the lab was a large limpet which had a microphone glued onto its shell and one of my occasional jobs was to sit on the wharf and listen to it feeding at high tide. Limpets are basically just a shell, a gut, a large foot and something a bit like a tongue covered in teeth called a radula which they use to scrape off algae from the rock. Charlie would bribe me with chocolate chippie biscuits to sit on the wharf for hours with a pair of headphones and a stop watch to count how many times a minute Mr Limpet ran his radula over the surface of his rock in an attempt to calculate how much biomass was required to sustain and keep the animal alive. Limpets may seem like a fairly innocuous shellfish, but they’ve saved many a shipwreck survivor from starvation and some 50 species are found around our coastline, including both marine and freshwater species.

Kim Westerskov was another character at the lab and he was already well known in Dunedin as the son of well known ornithologist, Kaj Westerskov. Kim spent many years at Portobello working on his doctorate studying the Foveaux Strait or Bluff oyster. These super yummy bivalves are also found in Otago Harbour and a number of other places. I remember there were some vicious rumours floating around at the time that, like the walrus in Lewis Carroll’s famous poem, Kim had eaten nearly all of the oysters in the harbour by the time he’d finished his doctorate. In actual fact Skeggs Fisheries, paid for much of Kim’s PhD and for many years they delivered big sacks of oysters to the lab so he could ‘study’ them! He was a very popular man! While he was working at the lab Kim and his colleague Keith Probert) also wrote “The Seas Around New Zealand”(1981) a comprehensive account of New Zealand’s seas and marine life and over the years he’s written and/or been the photographer for almost 20 books, many of them for children. He’s also completed photographic assignments for the BBC, TVNZ, New Zealand Herald and the New Zealand Geographic magazine among many others.

Chris Lalas was studying both local seals and shags and he was responsible for a lot of pioneering work on both species in the local area. This was at a time sea lions were rare visitors to the peninsula and the main seals you saw were fur seals basking on the rocks. It wasn’t until the mid-nineties that you started to see sea lions hauling themselves out onto local beaches and starting to breed. These days’ sea lions seem to be moving towards becoming the dominant seal species on the peninsula and anecdotally there is evidence of adult male sea lions actually targeting and eating young fur seals.

In those days the Portobello marine lab wasn’t just an academic institution. It was also the home of a very popular public aquarium but sadly this was forced to close in 2012 when the building it occupied was identified as a potential earthquake risk. While the public aquarium is now closed, the NZ Marine Studies Centre, which is part of the lab, remains open for pre-booked educational programmes and tours.

I used to love hanging out in the aquarium which was a very popular local attraction back then and I spent many happy hours watching all the animals. There was one big tank which ran the length of the entire wall and it contained some of the larger local fish including a big school of trumpeter. There were many smaller tanks filled with sea anemones, sea squirts, sea horses, bellows fish, and a whole range of small coastal marine life and another large tank which was always home to an octopus. One of my favourite, but admittedly rather ghoulish things to do, was to feed this giant super-intelligent mollusc. It could tell the second a crab entered the tank and its knobbly skin would run through a rapid kaleidoscope of colours and textures as it became increasingly excited. It was hard not to enjoy watching this consummate predator track down the poor animal before pouncing on it and enveloping it with its tentacles and breaking into the its shell with it’s parrot-like beak before sucking out the contents with a gleeful expression in its eyes. The following day all that would be left was the skeleton of the crab on the bottom of the tank. Octopuses are excellent escape artists and there were a number of times when the animal was found wandering around the lab, possibly looking for a mate or its next crab. As a budding naturalist anything that died in the aquarium was grist for my mill and at my own small museum I still have a number of specimens which I acquired from aquarium in those days including a dried billows fish and a giant spider crab. These are New Zealand’s biggest crab with a span of up to a metre. There was also a tank called the “touch tank” where visitors could put their hands into the tank and touch living specimens such as starfish, sea cucumbers, and other more sedentary marine life

I’m against zoos with cages full of imported animals but I do believe that marine education centres have an important place to play in the community because they’re often people’s first introduction to the marine world. I think many people see the ocean and its inhabitants as somehow not quite animal and they often don’t have the same level of empathy for marine species as they do for those on land. Fishes, sharks and octopuses all have brains, central nervous systems and consciousnesses just like us and they definitely feel pain. Marine education centres can help people to understand the complexity of both the animals themselves and the ecosystem they inhabit and learn to appreciate it. Many of our marine species are now under threat from the effects of over-fishing, pollution and climate change and the harbour is not the thriving pool of life it once was. While local marine life has suffered a decline the lab itself has turned from a tiny local research institute into a powerhouse of marine science and in 2017 a new five million dollar laboratory was opened on site.

——————————————————————————————-

Graham hit was diving with the South sea divers when he was taken by a white pointer shark at the spit .Dunedin club with twelve members. My dad was one of them.

Thank you for including a section about my late brother Charles Boyden’s work. He tragically lost his life whilst freshwater fishing near Greymouth in February 1979. Such a loss to the marine scientific world.

Mary Holmes.

Yes – I decided not to mention this so as not to upset anyone who knew him. He was a great guy and I very much admired him!